Nov. 25, 2025, TUCSON, Ariz. – A new study published in Geophysical Research Letters casts doubt on a 2018 discovery of a briny lake potentially lurking beneath Mars’s south polar cap.

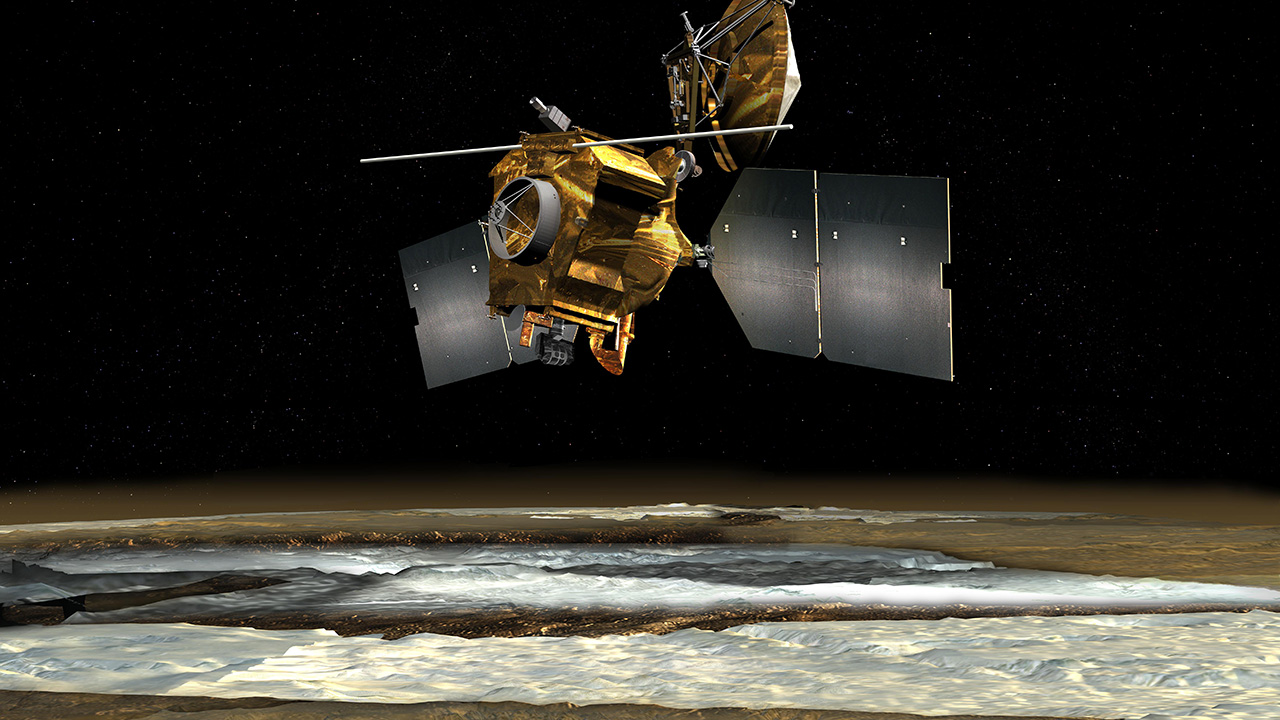

SHARAD, the Shallow Radar sounder on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), performed a maneuver that allowed it to peer deeper beneath the polar ice than ever before. It recorded only a faint signal where MARSIS (Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding), the low-frequency radar on the European Space Agency’s Mars Express spacecraft, found a highly radar-reflective surface under the ice in 2018, which that team interpreted to be due to the presence of liquid water.

“The existence of liquid water under the south pole is really compelling and exciting, but if it is there, SHARAD should also see a very bright reflectance spot, and we don’t,” said study lead author Gareth Morgan, a SHARAD co-investigator and Planetary Science Institute senior scientist.

SHARAD operates at a higher frequency than MARSIS. Higher frequencies can’t penetrate the subsurface as deeply as lower frequencies. To overcome this obstacle, the MRO team developed a new maneuver, called a Very Large Roll (VLR), to increase SHARAD’s power tenfold, allowing it to peer through the ice cap and reach what lies beneath.

“The two radars, SHARAD and MARSIS, are very complementary,” Morgan said. “We know there’s something special about the area, but moving forward, people need to find a solution that reconciles both findings, and this discovery provides critical information for the community to come up with new models.”

Serendipity on Mars

A VLR in this polar location can only be performed about once every two years. During a VLR, MRO rolls 120 degrees so that SHARAD’s view of the Martian surface is not obstructed by the spacecraft body. While this might sound like a simple task, it’s actually a logistical and physical dance that can only be performed at night – or more precisely, in Mars’ shadow – to protect the other sensitive onboard instruments from harmful solar rays and minimize the loss of power produced by the solar arrays.

“For most of Mars, that’s not a problem,” Morgan said. “But when you look at the poles, even though the South Pole is at night for half the year it can still be a problem. Because of its orbit, MRO will see the Sun a lot quicker than the ground beneath it, so we have to go into a roll, take the observation and come out of the roll before the spacecraft sees the Sun. The only time you can do that is for a short window around the Martian winter solstice.”

To complicate matters, the target area is only 12 and a half miles (20 kilometers) in diameter beneath a piece of polar cap roughly a mile (about 1,500 meters) thick. On top of that, Mars spins below MRO as its orbit takes it across each polar region with a narrow view of the surface below, and the opportunities for the ground track to cross the presumptive lake are limited.

“We’re really lucky that it all came together,” said Morgan. “All of these things had to align perfectly to pull this off.”

In October, the MRO team began a three-year extended mission that includes the use of SHARAD to continue probing Mars’ depths with VLRs, hoping to target features from volcanos to unusual equatorial deposits.

“VLRs are also critical for human exploration, because they can help us search for ice at Martian mid latitudes, where future human missions will likely land,” said coauthor Nathaniel Putzig, PSI associate director and senior scientist who serves as the SHARAD U.S. and deputy team leader.

“Cross-frequency investigations such as this will always be really important,” Morgan said. “It’s good to have both instruments, because then you’ve got two independent observations at different frequencies; the more frequencies you can throw at a problem, the better we can constrain properties of the Martian subsurface.”

Other authors include PSI Research Scientist Matthew Perry, the Smithsonian Institution’s Bruce Campbell and Jennifer Whitten, and Fabrizio Bernardini, a consultant who serves as the SHARAD Operations Manager for the Sapienza University of Rome, which leads SHARAD operations on behalf of the Italian Space Agency.