Isochrons for Martian Crater Populations

| ISOCHRONS FOR MARTIAN CRATER POPULATIONS OF VARIOUS AGES William K. Hartmann Page design: Daniel C. Berman |  |

BACKGROUND: USING CRATER COUNTS TO ESTIMATE AGES

Below you will find a text describing the basic principles behind the Planetary Science Institute system of utilizing crater counts and isochron diagrams in order to estimate crater retention ages of surfaces on Mars.

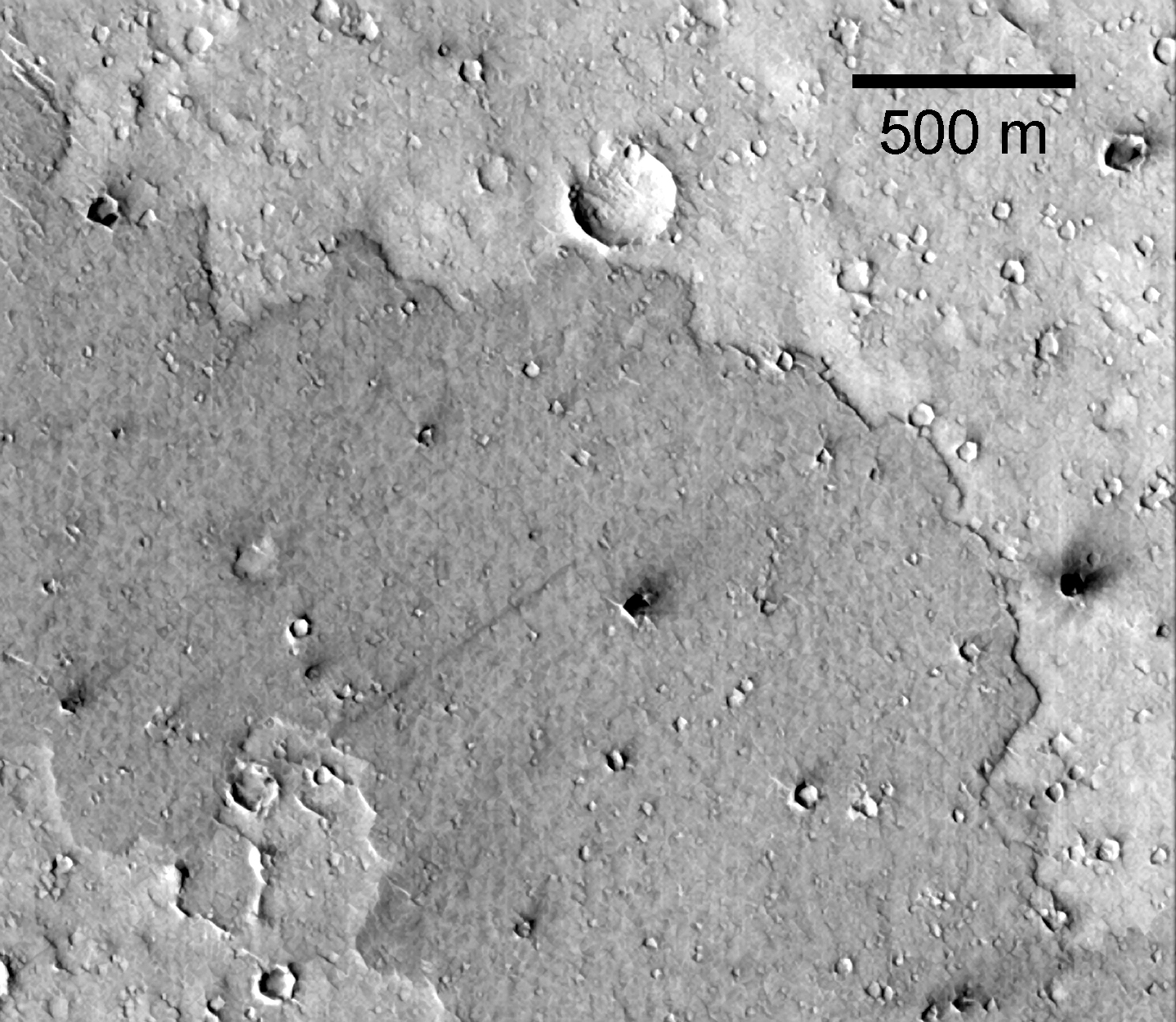

As discussed by Hartmann (1966) the crater numbers can date the actual formation age of a surface in an ideal case, such as a broad lava flow which forms a one-time eruptive event. The flow accumulates craters and the crater numbers date the time of formation. In other cases, not uncommon on Mars, the story is more complex. For example a surface may be covered by a few hundred meters of mobile sand dunes; the numbers of craters of diameter D and depth d would give a mean characteristic age of topographic features of the scale of D,d. Smaller craters in mobile dunes would disappear faster and have lower mean ages. In this sense, the derived age is a size-dependent Acrater retention age@ B the survival time of craters of given size. It is not quite a formation age in the sense of the lava flow age, but conveys tremendous information about the erosion/deposition/resurfacing environment of Mars.

Another example is exhumation, which is common on Mars (Malin and Edgett 2000, 2001). A surface could be formed and covered by sediments at some later time, degrading any craters on the original surface. Much later, the surface may be exhumed, as documented in various cases by Malin and Edgett. In an ideal case, such a surface might then show vestiges of the degraded original craters (indicating the duration of exposure of the first surface) and a second population of fresh, small, sharp-rimmed craters formed since the recent exhumation event. Malin and Edgett (2001, 2003), thinking in terms of dating the underlying process, asserted that such processes render Martian crater counts more or less useless for dating. On the contrary, such a situation can give extremely valuable estimates of the timescale of the exhumation processes, not to mention the timescale of exposure of the original underlying surface (which in turn is a lower limit to its age). Indeed, Hartmann et al (2001) found just this situation in the Terra Meridiani hematite-rich area, which they identified as a very ancient surface recently exhumed within the last few tens of My, because of the paucity of small, sharp-rimmed, fresh craters — an interpretation which appears consistent with observations from the 2004 Opportunity rover, which landed in this same general area on a sparsely cratered plain and found sulfate-rich sediments apparently eroding and leaving small, spherical hematite concretions which weathered out of the sediments as they eroded.

In general, however, in dating Martian units, we look for simpler situations where a relatively homogenous stratigraphic unit is identified, and which appears not to be contaminated by secondary-ejecta impact craters from any single, nearby, large fresh primary impact crater. We assume that in such a case, a gradual accumulation of primary impact craters and globally-averaged (or regionally-averaged) secondary ejecta craters will have built up a characteristic diameter distribution shape, sometimes called the “crater production function.” Usually we count all visible craters and test to see if the size distribution fits the so-called A crater production function B the size distribution previously measured for accumulated primary and secondary impact craters, globally averaged in the absence of erosion/deposition processes. If so, we compare the measured size distribution to the A isochrons derived below. An isochron is defined as a size distribution of all craters created, as described above, over a specified period of years, such as 100 My or 1 Gy.

INTRODUCTION TO THE SIZE DISTRIBUTION: SHALLOW BRANCH, STEEP BRANCH, AND TURNED-DOWN

The diagram we use to plot craters combines ease of use, maximum sensitivity to possible crater losses at particular sizes, and mathematical convenience (since, by mathematical coincidence, it has the same slope as a plot of cumulative number of craters vs. D). This diagram divides the D range into log intervals with base /2. For example, bin divisions include 500 m, 707 m, 1 km, 1.4 km, 2 km, 2.8 km, and so on. The vertical axis gives N = no. craters/km2 in each bin, and the horizontal axis gives D, divided as indicated above. The diagram is essentially a histogram, plotting the number of craters/km2 in each of these log-D bins.

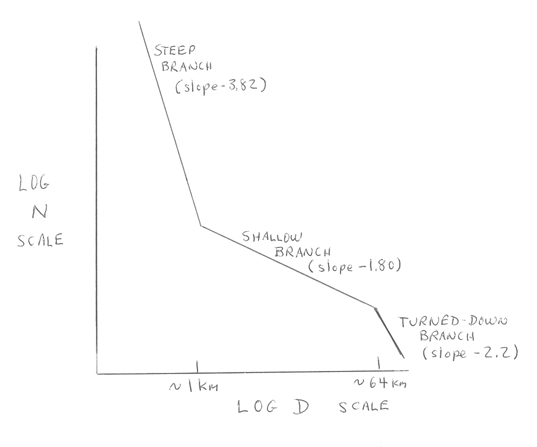

Figure 1 gives a schematic representation of the shape of a well-preserved, or A production, size distribution on this type of plot. In the text below, we will refer to three A branches of this size distribution. Historically, the first branch recognized was the shallow branch, at diameters above about 1-2 km, recognized from craters counted on telescopic photos of the moon. (See historical review by Hartmann, 2004, submitted to Icarus). This has been identified with the mix of asteroidal and cometary interplanetary fragments, and such craters are called A primary craters, connoting that they originate from cosmic debris falling from the sky at high speed. The first papers on diameter distributions of craters, meteoroids, and asteroids, fitted those distributions to power laws of the form N = k D-b and typically found b ~ -2 for lunar craters. The b value also equals the slope on our plot or on a cumulative plot. A more comprehensive study by the Basaltic Volcanism Study Project in 1981 give a least squares fit slope of -1.8 for lunar craters in this branch (Hartmann et al. 1981).

The second branch to be recognized was the steep branch, at D < ~1 km, first seen in 1964 when the Ranger probes gave the first sub-km resolution views of the moon. Shoemaker (1965) showed that secondary impact craters caused by ejecta from large lunar craters such as Copernicus, Langrenus, etc, fit this steep slope, and Shoemaker hypothesized that the small lunar craters in this branch are completely dominated by secondary ejecta from lunar craters. Hartmann (1969) showed from empirical data that fragments from low-energy-density disruption events (and craters made by them) are associated with the lower slope, while fragments from high-energy-density environments (such as hypervelocity impact crater transient cavities) associate with the higher slope, fitting this view. Hartmann and Gaskell (1997, p. 113) found a representative slope of -3.82 for this branch in the D interval viisible in lunar maria, about 1 km down to about 250 m, although further work is needed to understand the extent of local variations (if any) in the slope of the steep branch.

Strom, Neukum, and others eventually concluded that at the largest diameters, above 64 or even 100 km, the curve has a turned down branch.

At this point, Neukum (1983) made the reasonable decision to abandon the concept of multiple power law segments and simply fit the curve to a polynomial function. He developed a function which he has found to fit production-function craters on the moon, Mars, and asteroids (with appropriate scaling considerations).

Neukum and Ivanov (1994) challenged the Shoemaker-era conclusion and terminology, that the steep branch on the moon (or Mars) is associated with secondary ejecta from lunar (or Martian) primary craters. They found that the then-new high-resolution images of asteroids show a steep branch among sub-kilometer asteroidal craters B proving that the steep branch exists in space in the asteroid belt, suggesting in turn that even the A primary or cosmic impact craters on the moon and Mars, at these sizes, manifest the steep branch. In other words, they concluded that Shoemaker was not necessarily correct in assigning most sub-kilometer small craters to secondary impacts; they refer to the small craters as mostly A primaries in the sense that they could be cosmic. Hartmann (1999___) pointed out that this revision is somewhat semantic, because the steep branch found in the asteroid belt is presumably due to secondary ejecta from craters on asteroids B except that the pieces do not fall back onto the target asteroids but rather float in the belt and hit other asteroids. Thus, if the slope of the steep branch is controlled by crater ejecta (on one body or another) and if the crater ejecta size distributions are controlled by the mechanics of fragmentation in hypervelocity rock targets, the resultant slopes among lunar ejecta fallback, Martian ejecta fallback, and interplanetary asteroid ejecta may be negligible. Which is one reason that the size distributions among secondaries on in different environments deserve more investigation.

The log-differential plot is also more direct than a commonly-used type of plot introduced some years ago, called the Arelative plot@ or R-plot. This plots crater counts relative to an artificial -2 power law distribution (N = kD-2). It was introduced when the counters were dealing primarily with craters larger than 1 km, which roughly fit a -2 power law (more accurately, it is a -1.80 power law). Departures from the -2 power law were regarded as diagnostic. The problem is that we now count from D = 11 m up to multi-km sizes and the size distribution is much steeper at small sizes (power laws with slopes up to -3.____).

| SIDEBAR: COMMENT ON OTHER TYPES OF PLOTS This type of plot is called a log-differential plot It is better than the commonly-used cumulative plot of all craters larger than D, because it much more clearly shows losses of craters in any particular size bin. For example, if a certain region has had some erosive episode that removed all craters between 125 m and 500 m in size, the log-differential plot would show a dramatic downturn in that size interval, but he cumulative plot would merely flatten out. The cumulative plot produces an artificial smoothing of the data, which looks good, but comes at the expense of actual information-display about the data. |

ESTABLISHING THE AMAZONIAN, HESPERIAN, AND NOACHIAN ERAS ON THE CRATER-COUNT DIAGRAM

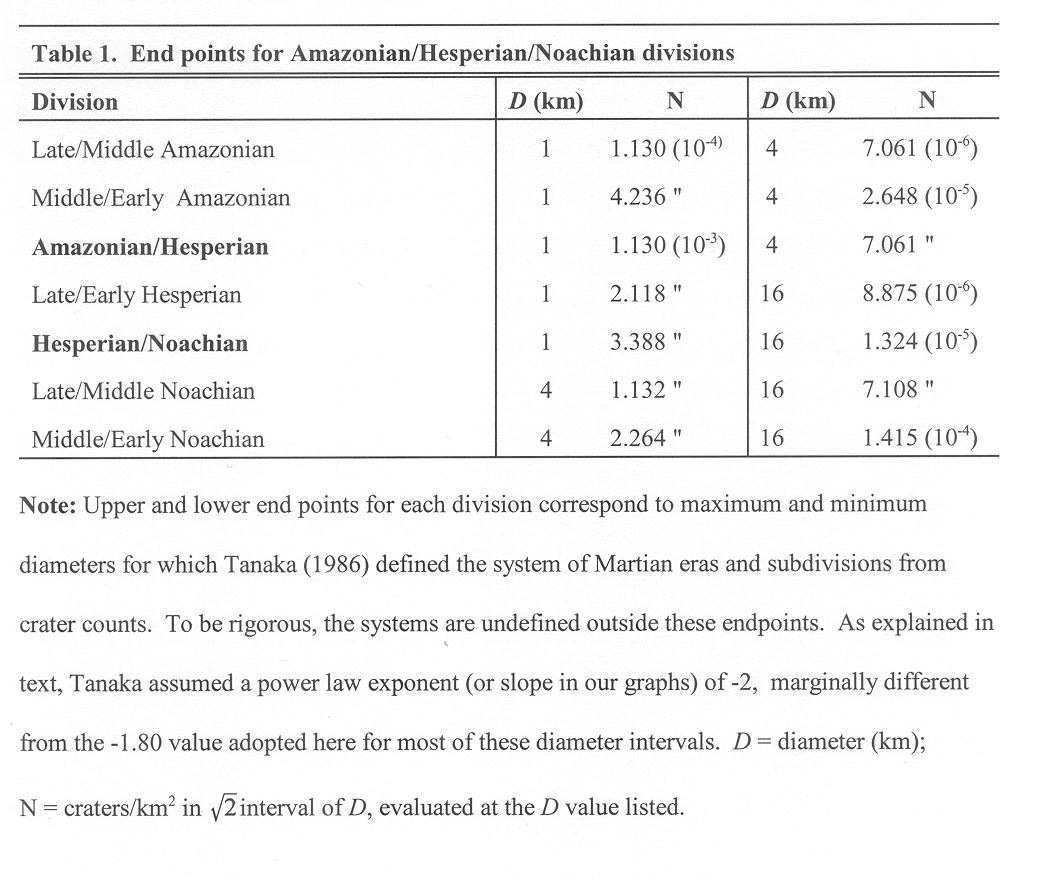

Tanaka (1986, Table 2) defined crater density limits to the Amazonian, Hesperian, and Noachian relative-age eras, based on the previous work of Scott and Carr (1978) and Condit (1978), for the purpose of stratigraphic mapping of Mars. That work parallels the development of terrestrial geology, in defining stratigraphy and relative time intervals long before the absolute time intervals could be measured. Tanaka defined each time interval in terms of cumulative counts of craters down to various diameters D, namely 1 km for the Amazonian and Hesperian, and 5 for the Noachian. Note that, in those post Viking years, diameter distributions had not been studied much below D = 1 km. (Even the major review of Martian cratering studies in 1992 by Strom et al. did not include discussion of crater counts below diameters of a few km, although some Viking images resolved craters of a few hundred meters in size.) Upper D limits for the definitions were D ~ 4 km above the Amazonian/Hesperian boundary, and 16 km for early Hesperian to early Noachian. In these definitions, Tanaka assumed a -2 power law for the diameter distribution in that diameter range, an early approximation to the -1.80 power law used in that D range in our data. [Note: In the -2 approximation, our log-incremental count in a diameter bin (D to /2D) is equal to the cumulative number given for all craters larger than D; for example, when Tanaka gives N = 160 craters/106 km2 for D > 1 km for the late/mid Amazonian boundary, we give 8.00 (10-5) craters/km2 for the log incremental count of craters in the interval 1.0 < D < 1.41 km (or, in Table 1, using Tanaka’s -2 power law, 1.13 (10-4) for the /2 log interval centered on D = 1.0 km)]. Applying these ideas and Tanaka’s diameter intervals in our system, we calculate the following curves, defining the boundaries of the stratigraphic eras in our graphical system (note Tanaka, 1986, divided the Hesperian only into late and early subdivisions):

| Late/mid Amazonian | log N (craters/km2) | = | -2 log D (km) – 3.947 (1 km < D < 4 km) |

| Mid/early Amazonian | log N | = | -2 log D – 3.373 (1 km < D < 4 km) |

| Amazonian/Hesperian | log N | = | -2 log D – 2.947 (1 km < D < 4 km) |

| Late/early Hesperian | log N | = | -2 log D – 2.674 (1 km < D < 16 km) |

| Hesperian/Noachian | log N | = | -2 log D – 2.470 (1 km < D < 16 km) |

| Late/mid Noachian | log N | = | -2 log D – 1.742 (4 km < D < 16 km) |

| Mid/early Noachian | log N | = | -2 log D – 1.441 (4 km < D < 16 km) |

These equations are used in Table 1 to calculate upper and lower endpoints of the diameter distribution segments used by Tanaka to define the eras, e.g., 1 to 4 km for the Amazonian/Hesperian boundary.

Figure 2 shows these curve segments, plotted in the format of the diagram we will use in presenting cratering data. The top solid line shows the level associated with saturation equilibrium of cratering, the maximum density that is reached. This was defined empirically for various solar system locations by Hartmann (1984) and tested experimentally by Hartmann and Gaskell (1977). Below this are shown the crater size distribution segments corresponding to Tanaka’s definition of the eras. Figure 2 emphasizes that the fundamental definitions of Amazonian-Hesperian-Noachian chronology is tied to topography with 1 to 16 km scale. The diagram in this form, lacking isochrons, is good for relative dating relative ages in the U.S.G.S. stratigraphic system, but gives no information on absolute ages.

[Figure 2] Basic format of Mars crater count diagram. Upper dark, solid line, gives steady state saturation equilibrium crater density, as confirmed empirically and theoretically by Hartmann (1984) and Hartmann and Gaskell (1997). Heavy, short solid lines define boundaries of Amazonian, Hesperian, and Noachian, as defined in the diameter D intervals used by Tanaka (1986, Table 2). Short, lighter solid lines mark the subdivisions of the Noachian (early, middle, late), Hesperian (early, late only two subdivisions were defined by Tanaka 1986), and Amazonian (early, middle, late), from the same source. This diagram is essentially a histogram, used to plot crater densities observed in each /2 D interval of crater diameter. We will derive isochrons showing number of craters/km2 in each created in each D interval, for specified surface ages.

The Isochron System: Basic Steps and Historical Review

Our basic approach to deriving Martian surface ages has been developed in a multi-step process in the papers already cited. Here we update and expand the derivation in a six-step process listed below, with item (d) being a new addition in this paper, and several other items being updated:

(a) Assume that the size distribution and time dependence of impactor flux are the same on Mars as on the Moon (to first order), and start with the crater size distribution measured in the lunar maria (averaging over various lunar mare surfaces), with adopted average age 3.5 Ga. (This is consistent with the conclusion of Hiesinger et al., 2003, that, volumetrically, most lunar mare lavas date from 3.3 to 3.7 Ga ago; also, an average of ages of 20 lunar basaltic units, based on Apollo, Luna, and meteorite ages, gives 3.51 Ga (Stffler and Ryder, 2001, Table V).

(b) Estimate the ratio Rbolide = ratio of meteoroids/km3 at top of Mars atmosphere relative to the Moon, for any specified meteoroid size. The term “bolide,” referring to luminous fireball phenomena in an atmosphere, is chosen to remind the reader that the Rbolide ratio is fixed only at the top of the atmosphere and that additional atmospheric losses must be taken into account. By (a), this ratio is assumed constant at all relevant sizes.

(c) Incorporate corrections for Mars/Moon crater diameter differences due to impact velocity and gravity scaling, and use these to…

(d) derive the size distribution expected on a hypothetical Martian surface of the same age as the average of the lunar maria.

(e) Make corrections for the loss of the smallest meteoroids during meteoroid fragmentation in the Martian atmosphere.

(f) Using the assumed average age of lunar maria and time dependence assumption from step (a), ~ 3.5 Ga, use the measured relation of cratering vs. age (from the Moon) to derive Martian crater density for Martian surfaces of other ages.

This process gives a set of predicted “isochrons,” or crater size-frequency distributions, for well-preserved surfaces of various ages, such as 1 Ga, 100 Ma, 10 Ma, and so on. The key is to think in terms of orders of magnitude; we want to distinguish 107 y surfaces from 108 y and 109 y surfaces in order to understand the gross planetary chronology. The system is not good enough to distinguish a 60 Ma lava flow from a 70 Ma flow, but that level of discrimination is less important at the current level of Martian scientific investigation.

Note again that we deal here with nearly the entire crater size spectrum. This contains more interpretive and chronological information than a simpler cumulative number of craters larger than some cutoff size, such as 2 km or 20 km, which is affected mainly by counts in the next two larger D bins. Also, the intervals used by Tanaka (1986) to define the Noachian, Hesperian, and Amazonian eras in terms of cumulative crater counts, namely 1 km < D < 16 km (see section 4 above) are useful in characterizing the gross “bedrock” geologic chronology, and establishing the overall Martian stratigraphy, but do not fully deal with the modification of old bedrock units by smaller-scale local obliterative processes, such as deposition of thin sediment layers, thin lava flows, and various sorts of erosion. Consider that the Canadian shield has a basal age of the order 109 y, while the 10-m and 100-m-scale features have much lower ages due to glaciation, sedimentation, and other processes. Mars has this same nature, and the full diameter range of craters conveys much more information than a specific restricted diameter range. For example, the rim height of 1 km crater is about 35 m, and thus a succession of very young Amazonian flows totaling >35 m thick can cover craters of D < 1 km and reduce the observed mean crater retention age of a broader mid-Amazonian plain if measured at topographic scales of a < 1 km, without removing craters of D > 2 km. Observed sub-kilometer structure would all be Amazonian, while the underlying multi-km structures would be Noachian (similar to the example of the Canadian shield, above). A correct interpretation of the area would rely on features that could be found only in the full size spectrum the older age from large craters and the young flows and their age from small-scale morphologies and the numbers of small craters. This situation is not uncommon on Mars.

Assumptions. To create isochrons for Mars, we make several assumptions that should be discussed further:

1) The size distribution of meteoroids hitting Mars is the same as that hitting the Moon (as mentioned in steps (a) and (b) above). We believe this should be true, since most dynamical effects are essentially size-independent. Meteoroid populations in the main belt in the size range .10 m and especially . 1 m may be significantly affected by the Yarkovsky and other effects, producing possible anomalies in both Martian and lunar crater diameter distributions below crater diameter D ~ 50 m and especially . 5 m, but this effect is probably similar on Mars and the Moon, and thus is minimized in the adoption of Rbolide (Farinella, et al., 1998; Hartmann et al., 1999).

2) The scaling corrections that will be used for impact velocity and gravity are diameter independent. A more detailed treatment might find a modest D dependence in these factors, but for our first-order discussion we assume that the Mars/Moon ratio of crater sizes formed by bolides of specified mass m is the same for all values of m.

3) The average impact rate ratio Rbolide between Mars and the Moon remains the same through time, if averaged over geological periods of time / 10 Ma. Individual asteroid breakup events could produce variations in the ratio over short time periods (fragment swarms on orbits that hit Mars and not Earth/Moon, or vice versa), but these should average out over periods longer than the dynamical half-life of fragments against ejection from the belt and collisions with planets (of the order 107 y), especially among the statistically more numerous smaller fragments.

Apropos assumption 3, the time dependence of the lunar cratering rate has been measured by several workers, and has been shown to be nearly constant within a factor ~ 2 averaged over the last 3000 Ma (Hartmann 1965, 1966b, 1970; Neukum, 1983; Grieve and Shoemaker, 1994; Neukum et al., 2001), so that crater densities are virtually proportional to age for ages younger than 3000 Ma. However, estimating the flux change in step (f) above, from the date of average lunar maria to 3000 Ma, introduces an uncertainty (as discussed by Hartmann and Neukum, 2001) estimated at a factor ~ 1.2 in either direction.

The greatest current uncertainty appears in step (b), in estimating Rbolide. This uncertainty is estimated as a factor ~ 1.5 below. These two uncertainties are probably the greatest in the system. Hartmann (1999) conservatively estimated the total age uncertainty as a factor of 2 to 4 in either direction, larger at small D < 100 or 200 m.

This approach is different from that of Soderblom et al. (1974) and Neukum and Wise (1976), who based their methods on assumptions about the decline of cratering at the end of the era of early intense bombardment 3.9 Ga ago, rather than on explicit estimates of the Martian crater production rate. Also, this approach has gradually grown in sophistication. Hartmann (1973) analyzed the Martian cratering rate relative to the lunar rate, based on then-available asteroid statistics and scaling relations, and estimated a Martian rate 6 times the lunar rate, for craters of multi-km size, with an endnote suggesting that new work might reduce this by a factor of 2 or 3 and increase the estimated ages. Hartmann (1977) more explicitly defined a parameter Rcrater = ratio of impact crater production/km2 -y on Mars relative to the Moon, estimating that it was around 2 for the multi-km craters that were known at that time. (This Rcrater concept was less sophisticated than thinking in terms of Rbolide, because scaling relations produce a size dependence in the apparent ratio of crater production at fixed crater size D. However, this approach had some validity in the 1970s when it could be applied only to a limited D range that could be represented by one power law, as will be understood in a moment.) The Basaltic Volcanism Study Project cratering team also adopted the Rcrater ratio and estimated that it lay in the range 1 to 4, with a best value of 2 (Hartmann et al., 1981).

These approaches yielded somewhat controversial ages of a few hundred Ma for late Amazonian geological units such as Tharsis volcanics, as early as the 1970s. The results began to look much more believable within about a year of the Basaltic Volcanism Study Project, with early recognition of Martian meteorites with ages of 1300 Ma (Wood and Ashwal, 1981; Nakamura et al., 1982; Bogard and Johnson, 1983). Wide acceptance of these as Martian igneous rock samples, however, and the acceptance that they constrained Martian chronologies, did not come for some years after that.

Starting with early Mars Global Surveyor image analysis, Hartmann (1999) reexamined the entire crater dating technique. He compared his power-law fit to the Neukum/Ivanov (1994) polynomial fit to the production function shape (log N vs. log D) and concluded that, at a first order level, the two fits were reasonably consistent with each other. The 1999 iteration adopted an “R” ratio of Mars/moon cratering of 1.6, with an uncertainty of plus a factor of 2 or minus a factor of 3, but ignored the effective D-dependence introduced by gravity and velocity scaling (see below).

As part of a larger Martian chronological study project (Kallenbach et al., 2001), Hartmann and Neukum [2001] collaborated to synthesize their systems, deriving new isochrons. This was done in collaboration with Ivanov (2001), whose data refined the Rbolideratio. Hartmann and Neukum curves were derived separately, to indicate the range of uncertainty inherent in the system. Hartmann and Neukum jointly placed the Amazonian/Hesperian boundary at 2.9 to 3.3 Ga ago (but with lower probability all the way from 2.0 to 3.4 Ga ago), and the Hesperian/Noachian boundary was better fixed (being constrained by high crater densities to the late stages of decline in early cratering) at 3.5 to 3.7 Ga ago. Significantly, they proposed the Late Amazonian Epoch began 300 to 600 Ma ago, constraining late Amazonian geologic features probably to the last 13% of geologic time.

Hartmann et al. (2001) attempted a synthesis of the Neukum and Hartmann systems by using a logrithmic average of the Hartmann power law production function (made of power law segments) and the Neukum/Ivanov Martian polynomial to study Martian impact gardening. Berman and Hartmann (2002) slightly modified the Hartmann/Neukum isochron curves and used an Rbolide estimate of 2.0 and Hartmann power-law curves in a 2002 iteration of the isochron system, which favored the curvature found by Neukum in the steep branch (see further discussion below).

The Isochron System: Derivation of 2004 Iteration

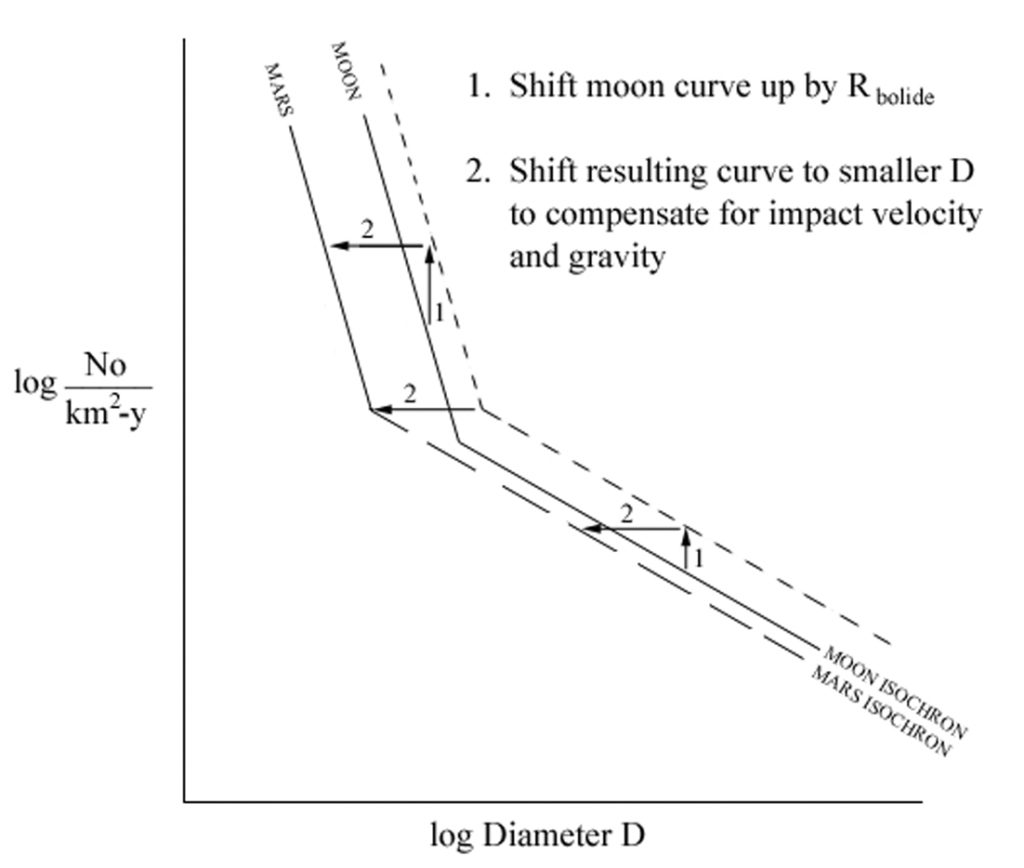

Improvements can still be made by using better estimates of the ratio Rbolide and the gravity and impact velocity scaling relations, and by adding the effects of loss of small meteoroids in the Martian atmosphere. To understand our approach to these improvements, think (for a moment) of the size distribution as constructed of power law segments (giving straight lines in the log N vs. log D plots used here). Virtually all work before MGS dealt with only one of these segments, the shallow or so-called primary branch, involving craters in the diameter range roughly 2 km < D < 64 km, where good statistics were available at that time. How do we use the lunar data from this diameter range to estimate the number of craters formed in that size range in a given time period on Mars? Imagine this diameter segment plotted for the number of craters formed in lunar maria in the last 3.5 Ga. To get the number of craters formed on Mars in the same period, Hartmann (1999) used the Mars/Moon cratering rate correction factor Rcrater to shift this segment vertically, because of a higher estimated cratering rate on Mars. In addition, impact velocity and scaling corrections altered the diameter of a crater produced by a given meteoroid, hence sliding the curve horizontally (to the left, to smaller sizes, because of lower Mars impact velocity and higher gravity). Taking into account the slope of the single power law segment, these two shifts were combined into an effective single vertical shift. Thus, that work assumed there was a single effective Rcrater ratio that shifted the curve vertically by a fixed amount along the whole diameter segment, and Hartmann (1999) applied it to the whole curve (11m < D < 100,000 m), deriving a single effective Rcrater value and shifting the whole curve vertically by that amount to convert from a lunar to a Martian isochron.

The modern extension of the Martian crater diameter distribution to both a shallow and steep branch makes this approach too simple, however. The problem, as seen in Fig. 3, is that the horizontal shift moves the intersection of the shallow branch and steep branch to the left, and has the effect of shifting the steep branch by a different net vertical amount than the shallow branch, so that the various power law branches (or parts of a polynomial fit in the style of Neukum) cannot be treated by a single vertical shift, nor does a single Rcrater value apply to the curve. Thus, the simple Rcrater concept loses its utility. In other words, the conversion from the lunar to Martian production functions is D dependent. These concepts were already dealt with in the treatment by Neukum and Ivanov (1994), who used scaling laws to examine the shape of the production function on other planets, and by Ivanov (2001), who discussed the Martian application. These concepts were also applied by Hartmann and Neukum (2001), and Hartmann’s 2002 iteration (unpublished) to derive isochrons from Neukum’s best estimate of the production function curve, and then independently from the Hartmann’s best estimate of production function, comparing results from the two approaches. Here, we begin our derivation of Martian isochrons by applying thee general scaling principles to the power law form of the crater size distribution, and also improve the treatment by Hartmann (1999) by using the latest estimate of Rbolide as a fundamental conversion parameter instead of Rcrater. We will present the stepwise derivation, starting with these lunar data, in Table 2, also discussed below.

[Figure 3] Schematic diagram showing the conversion of the production function measured on lunar maria to Martian conditions. The whole curve is shifted up to take into account the higher bolide impact rate on Mars. Then the curve is shifted left, to take into account the smaller crater size formed by each bolide, due to lower impact velocity and higher gravity on Mars. The net result is that the shallow or “primary” branch has a different net apparent vertical shift, or change in crater production rate, than the steep or “secondary” branch.

[Table 2]

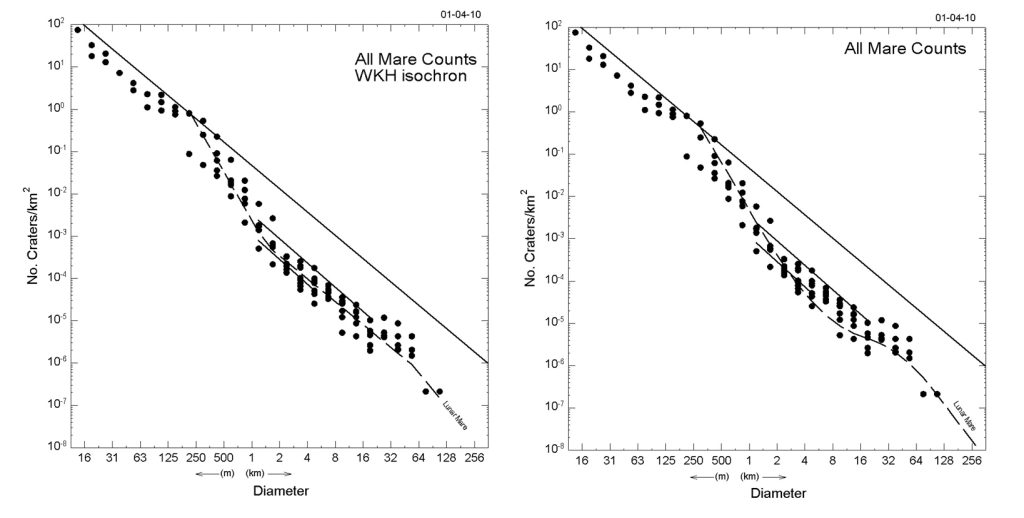

Step (a) in the above list is to determine the lunar mare crater diameter distribution. In the past I have primarily published only graphs summarizing the data. In this paper I use in addition a tabular summary, which allows the reader to utilize the original data. A summary of the direct counts summarizing of several lunar maria is given in column 2 of Table 2. These data are collected from a range of sources over many years. The include extremely detailed, multi-year cataloging of larger lunar craters (D > 4 km) by Arthur et al. (1963, 1965a, 1965b, 1966); counts of smaller craters are added by from my sampling of different maria (esp. Tranquillitatis and Cognitum, but also including parts of Imbrium and Fecunditatis), from Ranger, Surveyor, and Apollo data. Figure 4 shows a plot of these data, showing that at D / 250 m, they fit the power laws very well. (See further discussion in subsection A below.)

[Figure 4] Comparison of crater count data in lunar maria to (a) the power law fits of Hartmann and (b) the polynomial fits of Neukum. Data come from counts in all maria in 1960’s catalogs of Arthur et al., and from counts in various individual maria by the author. Mare craters go into saturation at D . 300 m and no information is available from the mare counts on shape of the production function size at the smaller sizes (see text).

Step (b) in our formulation is to improve the Mars/Moon impact ratio, Rbolide. A recent review of asteroid dynamics by Bottke (private communication, 2002) suggested a value of Rbolide ~ 3.15 (revised upward from his 2001 value of Rbolide ~ 2.76), and an independent review of observed Amor and Apollo asteroid statistics by Ivanov (2001) suggests Rbolide ~ 2.0. Bottke’s value includes a variety of populations, emphasizing asteroid dynamics but also taking into account estimates of comet populations and observations of Mars crossers. Ivanov’s is more empirical, based on observations of existing Mars crossers and Moon impactors of whatever origin. As a standard for our isochron diagram we adopt Rbolide for asteroids ~ 2.6 0.7. The uncertainty is a conservative estimate based on remaining uncertainties in the asteroidal and cometary fluxes, and is consistent with fluctuations in recent best estimates from the different authors. The uncertainty is important because it translates directly into a proportionate uncertainty in age, i.e., a factor of ~ 1.4.

Going from step (b) to step (d), the first task in correcting the lunar production function (craters/km2-y) to Mars is to recognize that each crater diameter bin corresponds to a particular bolide size and thus to raise (or lower) this curve by a factor Rbolide to correct for the increased (or decreased) number of bolides hitting Mars, as shown in the schematic diagram, Fig. 3. In Table 2, this step is combined with the impact velocity and gravity effects from step (c), as follows. We recognize that because, on average, each asteroidal or cometary bolide hits Mars at lower velocity than the Moon, and because Mars’ gravity is higher, the crater produced on Mars is smaller than the crater produced by the same size bolide hitting the Moon. These effects are treated numerically as follows.

Impact velocity effect.Crater diameter D goes approximately as impact kinetic energy E1/3.3 as reviewed by Baldwin (1963). Hartmann (1977) applied this, along with mean Mars and Moon impact velocities of 10 km/s and 14 km/s, respectively, to estimate that, due to this effect, a given bolide makes a crater that is

DMars/DMoon = [10/14]2/3.3 = 0.815.

This Baldwin-based result was then used by Hartmann (1999). However, the scaling laws given by Schmidt and Housen (1987) show D scaling as E0.43, so that

DMars/DMoon = [10/14]0.43 = 0.865,

which is used here.

Gravity effect. D goes approximately as gravity g-0.2 as reviewed by Hartmann (1977), who applied this value and estimated that, due to this effect, a given bolide makes a crater that is

DMars/DMoon = [373/162]-0.2 = 0.847.

This was used by Hartmann (1999). However, the updated scaling laws given by Schmidt and Housen (1987) show D scaling as g-0.17,, so that

DMars/DMoon = [373/162]-0.2 = 0.868,

which is used here.

Combining these two effects, we find that

DMars/DMoon = 0.865 / 0.868 = 0.751,

so that each bolide hitting Mars makes a crater 0.751 as big as it would have if it had had an orbital history that led to a collision with the Moon (Hartmann’s 1999 figure was 0.69). This effect is shown in the schematic diagram, Fig. 3.

The upshot is that if we know the crater size distribution which has accumulated on the Moon for a given period of time such as the craters formed on lunar mare surfaces in its average mare lifetime of about 3.5 Ga then we can derive the crater size distribution that would have been created on Mars during the same time by first shifting the lunar curve upward by the factor Rbolide, and then shifting it to smaller diameter by the factor DMars/DMoon ~ 0.751.

Because power laws produce linear segments on plots of log N vs. log D, it is conceptually easy to carry out this correction for each power law segment. The leftward shift to smaller diameter of any given linear power law segment is equivalent to a constant vertical shift along the whole length of the line by

d log N = -b d log D,

where N = no. craters/km2 in a log /2 diameter bin, D = diameter in km, and b is the slope of the power law segment. For example, with a -2 slope, a shift of the curve to smaller diameter by a factor by one log unit causes a decrease in apparent number by two log units. A shift of the curve to half the size causes a decline in apparent number by a factor 4.

Thus, if we have a value for the shift in diameter from DMoon to DMars, we can derive the corresponding vertical displacement (on the log N axis) of that whole power law segment of the production function on the log N – log D plot, as indicated in Fig. 3. Adopting Rbolide = 2.6 and the leftward shift in D by .751, we have d log N = log (2.6) – b log (0.751), or

d log N = 0.4150 + 0.1244 b

In the power law fits to the lunar curve, three branches have been identified (Hartmann, 1999): the traditional “shallow branch” (or “primaries”) measured from Earth-based photos, with slope -1.80, at 1.4 km < D < 64 km; the “steep branch” (or “secondaries,” as identified by Shoemaker, 1965) with slope -3.82 on the cumulative or log-differential plot, at D < 1.4 km; and the “turned-down branch” with slope -2.2 at D > 64 km.

We now give the equation defining each branch for the Moon and Mars. We will start with the shallow branch and the turned-down branch, which are easiest to derive, and then discuss how we fit the steep branch onto the shallow branch.

A. Shallow branch. For the lunar maria, the Basaltic Volcanism Study Project (Hartmann et al., 1981) derived a power law fit to available data:

log NMoon, shallow, mare = -1.80 log D – 2.920.

Neukum (1983) used a different approach and fit a polynomial function over a wide range of D, which produced more curvature in the shallow branch itself. Neukum continued to use a polynomial fit, deriving a relation that fit craters in lunar mare surfaces, lunar young crater interiors, and asteroids. Neukum and Ivanov (1994) used principles similar to those in this paper to convert this Neukum “universal” polynomial function to Mars, and Neukum et al. (2001) and Hartmann and Neukum (2001) discussed in detail the further application of polynomial and power law functions to Mars.

In the present work, we critically examined the fit of the data for the lunar mare shallow branch to the polynomial and power law functions proposed earlier. Figure 4a shows a comparison of observed lunar mare crater diameters data from the Arthur catalog of the 1960s (Arthur et al., 1963, 1965a, 1965b, 1969) and from my own later counts on Maria Cognitum, Tranquillitatis, and to a lesser extent Imbrium, Oceanus Procellarum, and other maria, to the power laws used here. Figure 4b shows a comparison of the same data to the Neukum universal polynomial curve. The Arthur et al. and Hartmann data show less curvature than the Neukum function in the multi-km range, and fit a power law (straight line in this format) in this range. To develop the Martian curve, we thus adopt the power law with a slope of -1.80 for this diameter region to give a mean lunar mare function for our step a.

Using the slope -1.80, the combination of shift upward by 2.6 and leftward by 0.751 in D corresponds (by the above equation) to a net upward shift in N by Δ log Nshallow = +0.1911. Thus we have

log NMars, shallow, 3.5 Ga = -1.80 log D – 2.729

B. Turned-down branch. On the Moon this branch begins at about 64 km, but the shift to smaller D on Mars by 0.751 gives a beginning diameter of D ~ 48.1 km. With an assumed slope of -2.2 for this branch, the intersection with the above law at D = 48.1 km gives:

log NMars turned-down, 3.5 Ga = -2.2 log D – 2.056

C. Steep branch. In the 1999 iteration of the isochrons, Hartmann (1999) used simply a power law with a slope of -3.82, a slope which had been measured for the Moon (Hartmann and Gaskell, 1997, p. 113) an approach similar to that used above for the shallow branch. This was applied at D #1.414 km, and the 1999 equation was

log NMoon, steep,, mare = -3.82 log D – 2.616 (D < 1.414 km).

However, the measurable data for the lunar mare steep branch apply primarily only down to D ~ 250 m, because the lunar maria are saturated with craters below that size (Hartmann, 1984; Hartmann and Gaskell, 1997). Thus the shape of the production function curve below 250 m is not well determined from the lunar mare data and deserves more attention. Also, the 1999 lunar equation gave values systematically lower than lunar mare counts in the specific region 250 m-1 km (by a factor around 1.9), though the fit is better when including the D bins just outside that region). Close examination of the fit in that region leads us to match the two curves at D = 2.0 km rather than 1.414 km, and adopt a new equation for the lunar steep branch in the range 250 m < D < 2.0 km,

log NMoon, steep, mare = -3.82 log D -2.312 (Valid at 250 m < D < 2.0 km)

This curve is shown in Table 2, column 3.

The problem now is how to fit the steep branch curve below 250 m to Mars (down to the MGS crater resolution limit of 11 m). In the 1999 work, we simply extrapolated the -3.82 power law to these small diameters, as is done in Table 2, column 4. In many Martian areas, however, we have found the observed diameter distribution curving slightly toward shallower slopes at small diameters, i.e., a deficiency at small crater sizes, which we attributed to obliteration losses among small craters by erosion, deposition, lava flows, etc. (Hartmann and Berman, 2000; Berman and Hartmann, 2002). Neukum, however, has argued that he can trace the steep branch production curve downward into the decameter range by counting on interiors of young craters and fitting those data to segments defined by older surfaces. By fitting the entire diameter range of data to a single polynomial, Neukum thus found a downward curvature toward small diameters below 250 m. The Martian data suggest that including Neukum’s curvature in the production function gives a better description of the isochrons than a simple power law extrapolation at D < 250 m.

[To put this in historical context, the power laws were utilized by Hartmann in the 1960s as a convenient approximation, partly because power laws had been introduced to lunar crater discussions by Young (1940) when only the shallow branch was known, and partly because power laws had been used to fit asteroid and meteorite size distributions (Hawkins, 1960; Brown, 1960), and also because experiments gave approximate power law size distributions, as discussed by Hartmann (1969). No claim was intended that a power law is necessarily or a priori better than another fit. In any case, it is always risky to assume that downward curvature is due to the production function, because preferential losses of small craters are expected due to erosion. Nonetheless, considering all these influences, Hartmann et al. (2001) and the “2002” iteration (Berman and Hartmann, 2002) attempted to utilize aspects of the Neukum curvature in the steep branch. Here again, I have chosen the Neukum data, as converted to Mars by Neukum and Ivanov, for an improved shape of steep branch below D = 250 m.]

In the lunar maria, the intersection of the steep and shallow branch was at 1.4 to 2.0 km, but this should move to the left by a factor 0.751 on Mars, giving an intersection at D = 1.05 to 1.50 km. To fit the Neukum-Ivanov curve onto the Hartmann curve we could have forced an intercept exactly at D = 1.05 or 1.50 km, but instead we adopt the measured slope of -3.82 at 250 m < D < 1.4 km (Hartmann and Gaskell, 1997, p. 113), and give weight to all the data points from my own lunar crater counts (D > 250 m). Thus we derive

NMars, steep, 3.5 Ga = -3.82 log D – 2.372 (for the range 250 m < D < 1.4 km),

We fit the Neukum-Ivanov Mars curve onto this Hartmann predicted Mars “stem” curve, giving a steep branch that fits our observed lunar diameter distribution down to 250 m, but preserves the curvature of the Neukum “universal” production function diameter distribution at D < 250 m. The resulting isochron shape is listed in Table 2, column 5.

Adjustment of the steep branch for losses of small meteoroids in the Martian atmosphere. Step (e) is a final improvement, made for the first time in this iteration, is made by allowing for breakup and loss of small meteoroids in the Martian atmosphere. They are thus considered lost to the Martian cratering record. As Popova et al. (2003) show, the breakup is dependent on meteoroid taxonomic type, and is more important for icy comets and weak stones than for strong stones and irons. Small fragments are reduced to subsonic speeds and do not create “normal” hypervelocity impact explosion craters. Using estimated data for numbers of different meteoroid types (3% irons with very high strength, 29% ordinary chondrites with strength 25 bars, 33% weak stones like carbonaceous chondrites with strength 5 bars, and 35% weak icy bodies with strength ~ 1 bar), Popova et al. (2003) graphed a corrected size distribution of craters expected under the current Martian atmosphere. Popova (private communication, 2003) used this formalism to gave a detailed calculation for these effects as a function of D, used here. Table 2, Column 6, gives Popova’s calculated data for losses of small craters as a result of meteoroid loss in the Martian atmosphere, and column 7 [= (column 5) / (column 6)] gives the final estimated production function of craters on a Martian surface of age 3.5 Ga.

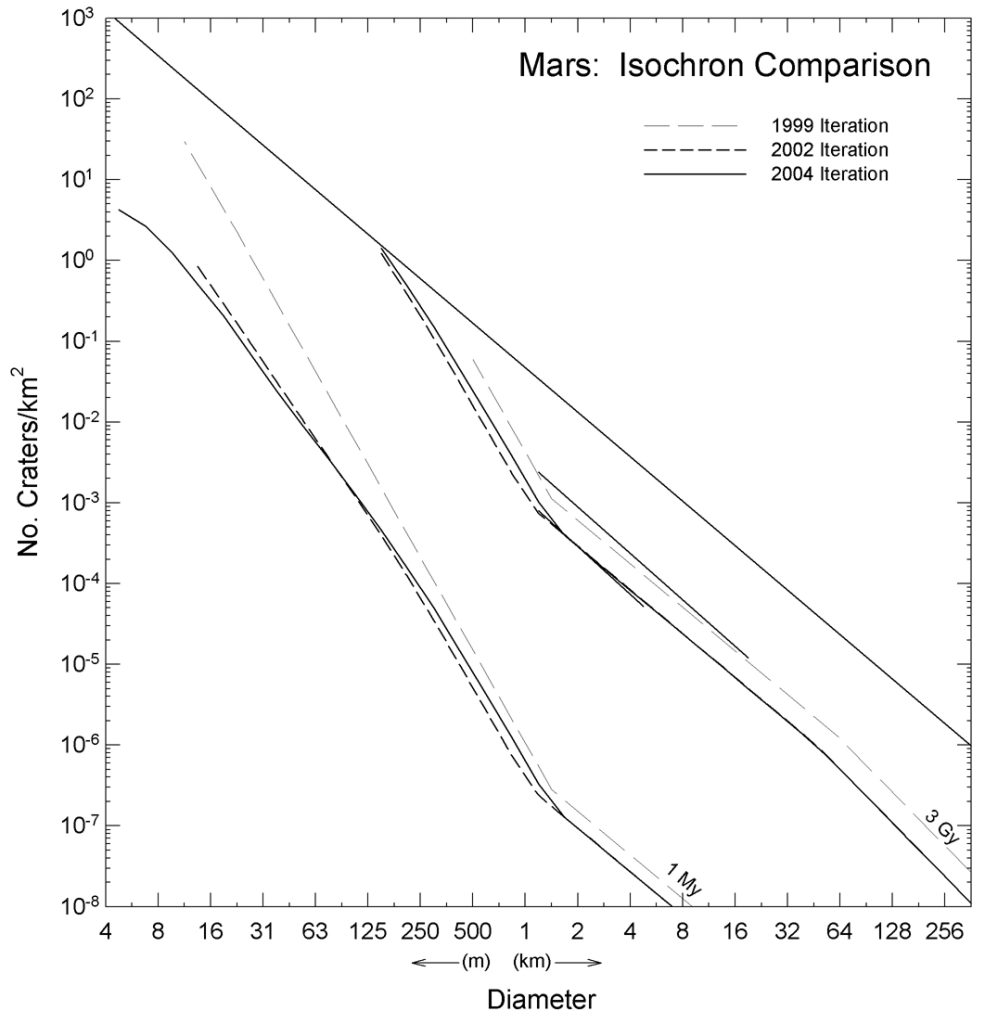

As can be seen in Fig. 5, the main variation between the 1999 and later models occurs at D < 250 m, and becomes important for surfaces younger than a few Ga. Older surfaces reach saturation at D < 250 m, masking these differences. Figure 2 emphasizes that the main uncertainties are for small craters on young surfaces. For surfaces younger than a few Ga, change from -3.82 power law in the 1999 steep branch to the Neukum curvature in the 2002 and 2004 iterations was the major change, increasing inferred ages by an order of magnitude for crater counts at the smallest scale, below about 60 m. Hearteningly, the change from the 2002 to 2004 iteration is minimal, being within the typical uncertainties of the crater counts at small sizes. The correction to the 2002 Hartmann curve shape is only ~ 10% at D = 31-63 m, but grows to a sizeable factor 2 difference in the smallest bin at which we count craters (11 m < D < 16 m). This illustrates the need for counts over a wide D range whenever possible. As shown in Fig. 5, the Popova effect begins to dominate below that, since we predict that hypervelocity cratering will cease below D ~ 0.1 to several meters (being from irons at the smallest sizes). In order to dramatize the loss of small meteoroids, Fig. 5 is the only figure in this paper to extend the diameter distribution down to D = 4 m. The most dramatic effects on crater loss occur below D = 11 m, i.e., below the normal cutoff for our crater counts, based on MGS resolution.

[Figure 5] Comparison of isochron shapes from current and previous iterations, showing isochrons for 3 Ga and 1 Ma. Differences between the iterations are less than or comparable to the scatter in crater counts for typical stratigraphic units, except for young surfaces at small diameters, below D ~ 125 m. The difference from 1999 to 2002 iteration is due mainly to introduction of the “Neukum curvature” in the steep branch at small sizes, and the smaller difference from 2002 to 2004 is due mainly to the “Popova effect” loss of small meteoroids in the Martian atmosphere, affecting craters primarily at D . 31m.

The above approach (Table 2, column 7) gives an isochron for Mars for any surface with age equal to the effective average age of lunar maria. In Hartmann and Neukum (2001) we took this average age to be 3.4 Ga. I adopt here a mean age of 3.5 Ga for the surfaces I have counted, as discussed in step (a) above. [Note: The Neukum time dependence (see equation below), shows ~ 14% difference in total crater density accumulated since 3.5 Ga as opposed to 3.4 Ga, a small change compared to the uncertainty in R.)

Step (f) is to convert the 3.5 Ga isochron to isochrons for other ages, using the dependence of cratering as a function of time, as measured in the Earth/Moon system. This time dependence has been interpreted as a product of scattering of the earliest planetesimals among the planets throughout the inner solar system, and since planetesimals are scattered by planetary encounters on timescales ~ 20 Ma, Mars is unlikely to have had a radically different time dependence than that measured in the Earth/Moon system. Hartmann (1965a, 1965b) showed that the Canadian shield cratering implied an age of the order 3-4 Ga for lunar maria, and that this in turn required a much higher cratering rate prior to 3.5 Ga, with a decay since then, and this result was confirmed by lunar samples. Neukum (1983) and Neukum et al. (2001) give a particularly useful quantitative version of this decay of flux as a function of time, based on analysis of crater populations at different lunar landing sites. Neukum’s resultant accumulated number of craters/km2 formed since time T (in Ga) is assumed to have the same time dependence at all sizes, and as expressed for lunar craters larger than 1 km the time dependence is

ND>1 km = 5.44 (10-14) [(e6.93T) -1] + 8.38 (10-4)T

This formulation shows that the total accumulated crater density for 3.5 Ga lunar maria should be 1.86 the density for a 3.0 Ga surface, and 5.76 the density for a 1.0 Ga surface. The 3.5 Ga isochron derived above is thus converted to isochrons for 3.0 and 1.0 Ga using those ratios, as shown in Table 2, Columns 8 and 9. Because the measured cratering rate (averaged over geologic time) has been essentially constant since 1.0 Ga ago, the ages for younger surfaces are proportional to these data. In columns 7, 8, and 9 the isochrons at the smallest diameters, D . 31 m, are regarded as an approximation based on extrapolation of the Neukum production function.

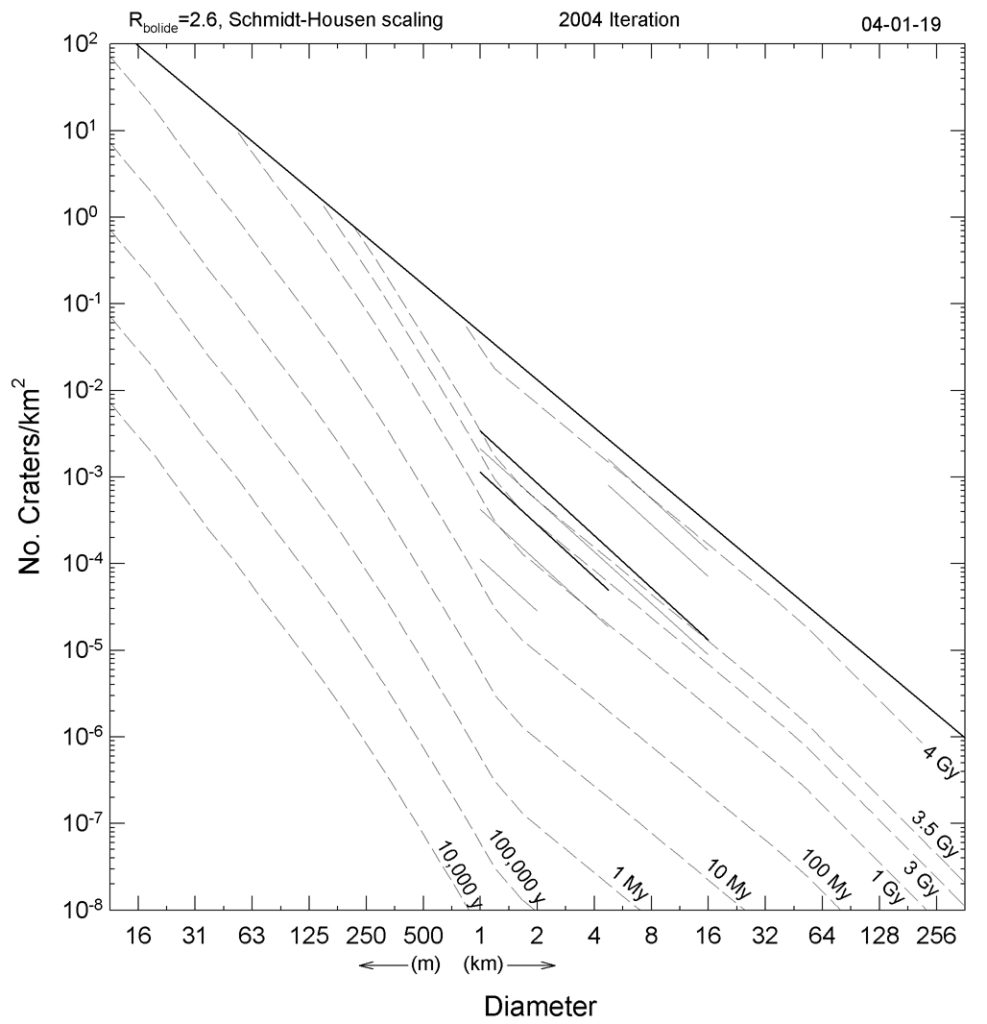

Figure 6 shows the final diagram, the 2004 iteration of the Martian crater diameter distribution isochrons for ages from 10,000 y up to 4 Ga.

[Figure 6] Final 2004 iteration of Martian crater-count isochron diagram. Upper solid line marks saturation equilibrium. Heavier short solid lines (1 km < D < 16 km) mark divisions of Amazonian, Hesperian, and Noachian eras; lighter nearby solid lines mark subdivisions of eras all based on definitions by Tanaka (1986). Uncertainties on isochron positions are estimated at a factor ~ 2, larger at the smallest D . 100 m (total uncertainties in final model ages, derived from fits at a wide range in D, including uncertainties in counts, are estimated a factor ~ 3).