Aug. 5, 2025, TUCSON, Ariz. – Researchers have studied a new mineral on Mars, called ferric hydroxysulfate, that could provide insight into how heat, water and chemical reactions shape the planet’s surface, according to a new paper published in Nature Communications.

Scientists identify minerals on other planets using spectral data, which show distinct patterns of reflected light depending on a target’s crystal structure and chemistry. For decades, while studying the Martian surface, they tried to understand a specific spectral signature unlike any produced by known minerals.

“People had seen that signature in the data before, but hadn’t conducted detailed studies about how it formed and what caused it,” said Catherine Weitz, a co-author on the study and senior scientist at the Planetary Science Institute.

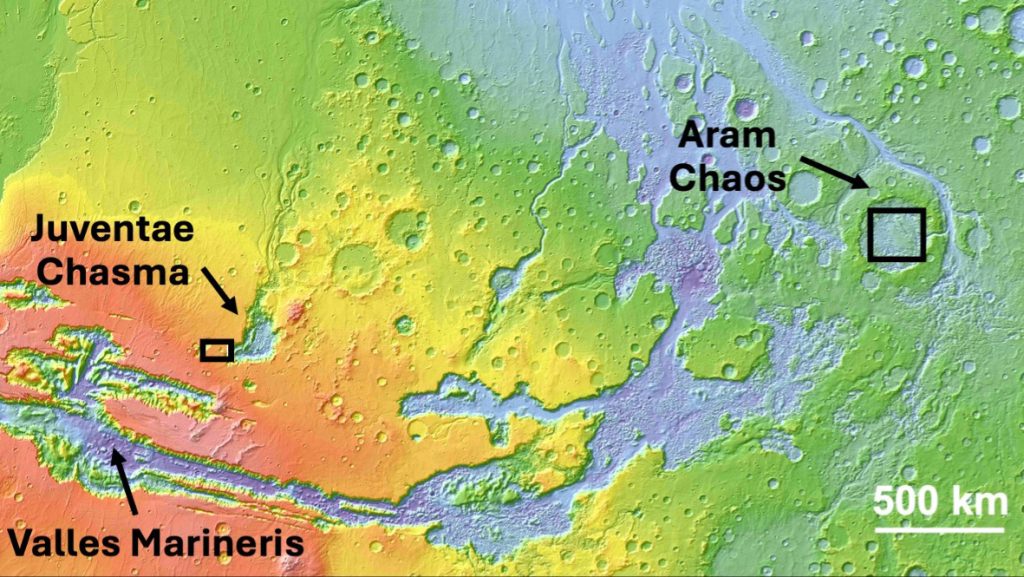

This investigation focused on two sites near the vast Valles Marineris canyon system bearing this unidentified spectral signature: a plateau above the three-mile-deep Juventae Chasma, and Aram Chaos, where ancient water drained away toward regions in the north. One site is at a high elevation and one is low within a large older crater.

“These are two very different geologic environments,” Weitz said.

At the Juventae Chasma plateau, there are signs of ancient water channels across the landscape, but scientists found sulfates in just one small, low-lying spot.

Sulfur is common on Mars and combines with other elements to form minerals, especially sulfates. While most sulfates readily dissolve on Earth during rainfall, on the dry Martian surface, these minerals can survive for billions of years. All sulfates have distinct spectral signatures that can be identified from orbit using the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, or CRISM instrument, a spectrometer onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

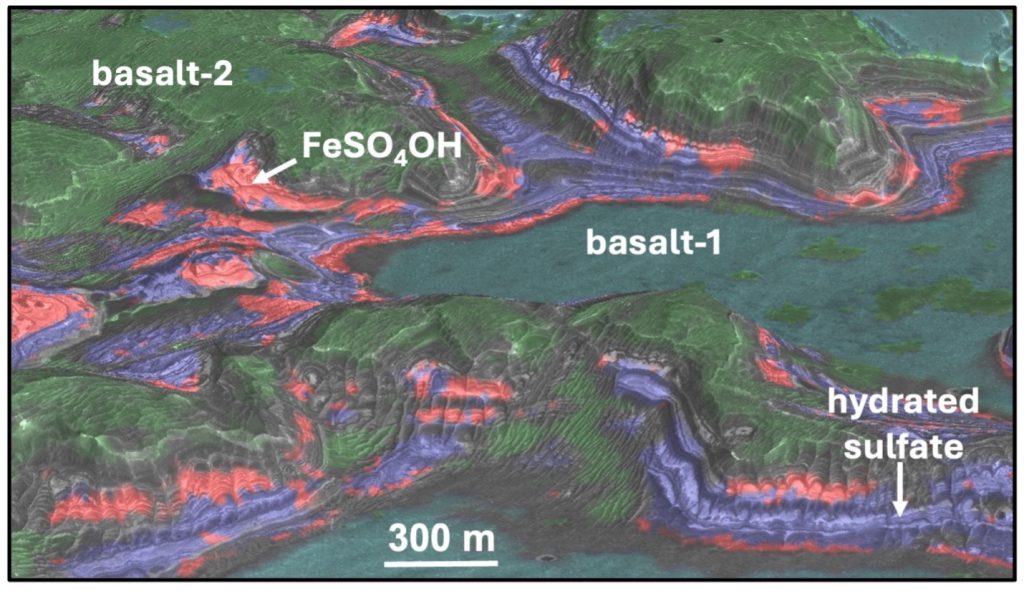

The sulfates found at the plateau were likely left behind when pools of sulfate-rich water slowly dried up, forming what’s called polyhydrated sulfates. The new ferric hydroxysulfate mineral was found surrounding these polyhydrated sulfate deposits and sandwiched between basaltic, or volcanic, materials. This suggests that lava or ash heated the polyhydrated ferrous sulfate to create the new mineral at Juventae, the researchers suggest.

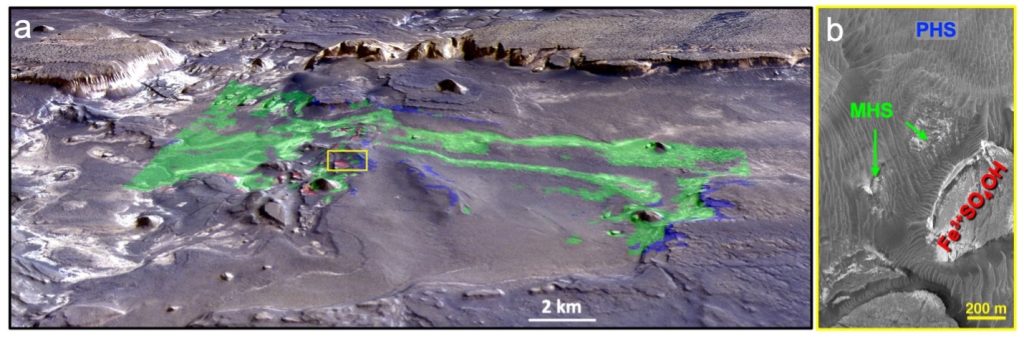

The other site, Aram Chaos, is characterized as a chaotic terrain because scientists believe it was carved and shaped by powerful floods in the past. As water gradually dried up, it left behind iron and magnesium sulfates. At Aram Chaos, the upper layers of sediments contain polyhydrated sulfates, while the monohydrated sulfate and ferric hydroxysulfate layers lie beneath.

The team was puzzled by these findings, so they sought to reproduce them in the lab, which has not been done previously.

There, tests showed that heating polyhydrated sulfates produces monohydrated forms, and heating above 122-212°F (50-100 °C) produces the ferric hydroxysulfate. This suggests that geothermal heat caused the minerals to transform at Aram Chaos whereas volcanic heating by ash or lavas caused the heating at Juventae.

Monohydrated and polyhydrated sulfates occur across broad regions on Mars, including at the Curiosity rover site in Gale crater, while ferric hydroxysulfate is so far limited to only a few small regions. The presence of ferric hydroxysulfate indicates locations where there was heat to transform the sulfates.

“Our experiments suggest that this ferric hydroxysulfate only forms when hydrated ferrous sulfates are heated in the presence of oxygen,” said postdoctoral researcher Johannes Meusburger at NASA Ames. “While the changes in the atomic structure are very small, this reaction drastically alters the way these minerals absorb infrared light, which allowed identification of this new mineral on Mars using CRISM.”

Today, Mars has a thin atmosphere mostly consisting of carbon dioxide, but still has enough oxygen for this reaction to proceed and for oxidation of other forms of iron as well.

“The material formed in these lab experiments is likely a new mineral due to its unique crystal structure and thermal stability,” said lead author Janice Bishop, senior research scientist at the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center. “However, scientists must also find it on Earth to officially recognize it as a new mineral.”

Temperatures above 122°F are much hotter than what Mars now experiences at the surface. The sulfates at Aram Chaos and the Juventae Plateau, including the ferric hydroxysulfate, likely formed more recently than the terrain in which they occur, possibly during the Amazonian period, less than 3 billion years ago. This study reveals that heat from both volcanic activity at the Juventae Plateau and geothermal energy below Aram Chaos can transform common hydrated sulfates into ferric hydroxysulfate. The findings suggest parts of Mars have been chemically and thermally active more recently than scientists once believed, offering new insight into the planet’s dynamic surface and its potential to have supported life.

“There may be other places where we see this sulfate, and we want to look more closely at those locations,” Weitz said. “On the other hand, it could be exciting to find ferric hydroxysulfate signatures in places where we don’t expect it, because then we’d have to think about how those locations got warm enough to form it.”

Rebecca McDonald

SETI Institute Director of Communications

[email protected]