A decade ago this week, NASA’s New Horizons mission snapped the first-ever close-up image of Pluto. The awe-inspiring portrait of the dwarf planet featured a heart-shaped plane of frozen nitrogen and methane, which was soon after named Sputnik Planitia.

The Planetary Science Institute is home to scientists present for the July 14, 2015 flyby of Pluto and subsequent image reveal at Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, or APL. This week, they returned to APL to meet with other planetary scientists and to discuss the advances made since the Pluto flyby.

They also reflected on their own flyby experiences and connections with the incredible science coming out of the mission.

PSI Senior Scientist Carly Howett remembers the image reveal as a once-in-a-lifetime memory. She is also now the PI of the Ralph instrument on New Horizon’s extended mission.

“It was exhausting and exciting, terrifying and exhilarating, just like exploration is supposed to be. Now, 10 years on, that wondrous moment feels like a lifetime ago, but the part of me that Pluto shaped is alive and kicking, and I know it is for all the other people Pluto touched. New Horizons showed me what true exploration feels like, and for that I will be forever grateful and forever excited to explore further.”

PSI Research Scientist Kirby Runyon knew since high school that he’d find his way onto the mission. By the flyby, he was a third-year graduate student helping support the mission scientists with small errands.

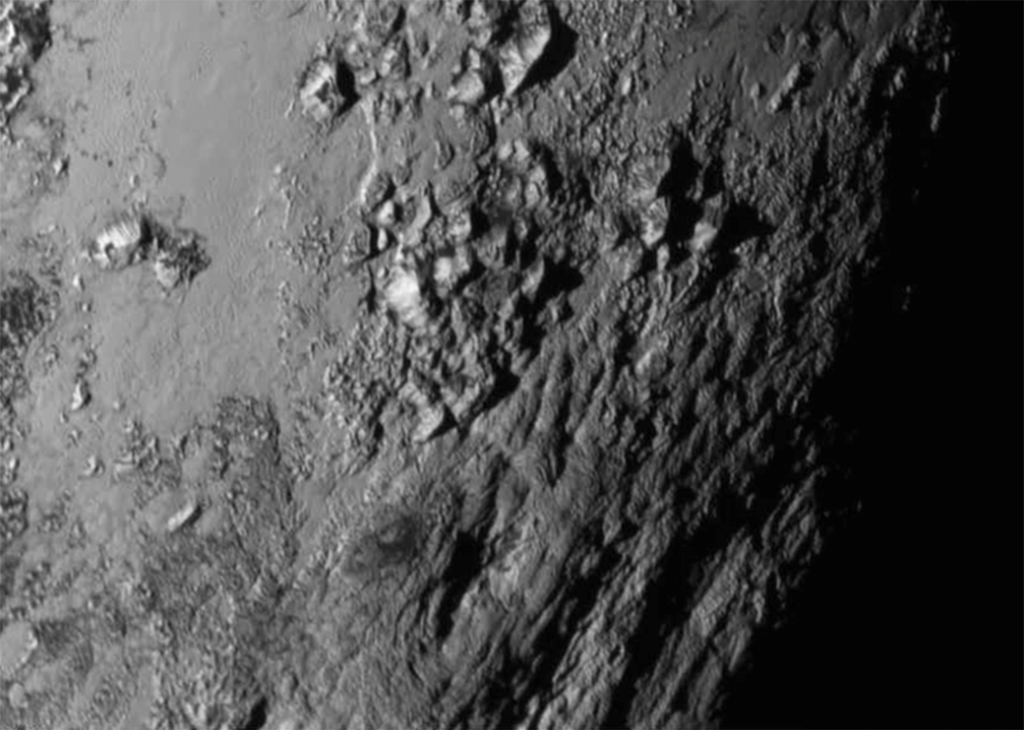

He remembered seeing the “amazing” first full image of Pluto, but said it was the close-up images – especially those of Pluto’s mountains, revealed a day or two later – that gave him chills. Soon after, he was present for the naming process.

“They printed off the full image of Pluto, and we had a database of names, but the names weren’t assigned to any features yet,” Runyon said. “So, people would pick a name off the database, circle a feature that no one has ever seen before on the map and just name it. That experience just reminded me of Adam naming all the plants and animals in Genesis. It just felt like we were doing our God-given task of exploring.”

Runyon eventually graduated with his doctorate and joined APL where he was funded for mission work. Later, he moved to PSI where he remained an unfunded team member.

PSI Senior Scientist Susan Benecchi also found her way onto the mission in graduate school, during which her advisor was part of the New Horizon team. She is now a science team member on the New Horizon’s extended mission.

“The mission has always been good about training and bringing up the next generation of scientists,” Benecchi said.

During the flyby, she was part of the team planning New Horizon’s next targets, such as small Kuiper Belt object Arrokoth, which New Horizons imaged in 2019. Arrokoth, they learned, is an 18-mile-wide binary object.

“New Horizons kind of reset our understanding of the outer Solar System,” Benecchi said. “From Pluto, Arrokoth and also from the other objects we looked at, the geology of these objects is much more active than we ever imagined. We used to think of them as ice balls at the edge of the Solar System. So, it’s a really interesting science project.”