Dec. 1, 2025, TUCSON, Ariz. – From Europa to other icy moons, scientists are studying how surface features form and what they might reveal about the potential for life.

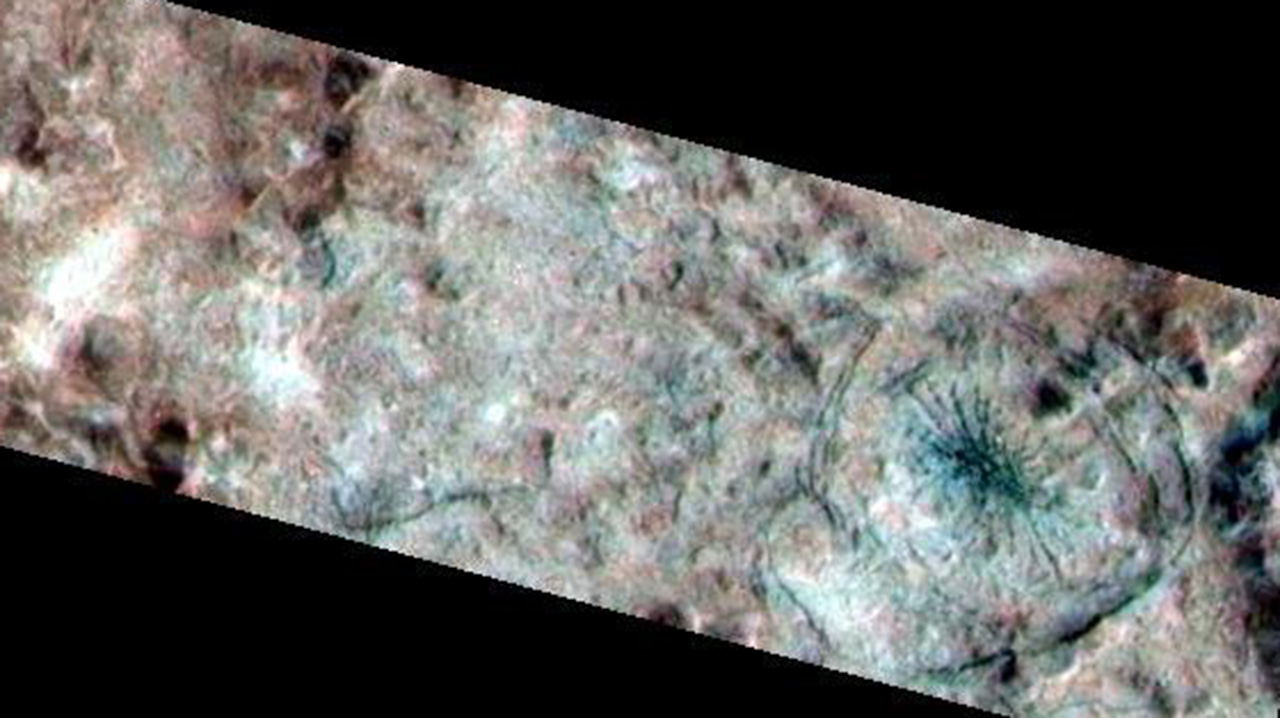

In a new study published in The Planetary Science Journal, researchers from the Planetary Science Institute, the University of Central Florida, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) and other institutions explored a unique, spider-like feature in Manannán Crater on Europa, one of Jupiter’s icy moons.

“This spider-like feature might have formed through the eruption of melted brines following the Manannán impact,” said coauthor Elodie Lesage, a PSI research scientist. “This would mean that it can inform us on subsurface properties and brine composition at the time of the impact.”

The lead author, UCF’s Lauren Mc Keown, and her team also study Martian ‘spiders,’ which are branching, tree-like features that form in the regolith near Mars’ south pole. They applied that knowledge to other planetary surfaces, including Europa. While Martian spiders form when dust and sand are eroded by escaping gas below a seasonal dry ice layer, the team’s Europa work asserts that the “asterisk-shaped” feature may have formed after impact.

“Lake stars [on Earth] are radial, branching patterns that form when snow falls on frozen lakes and the weight of the snow creates holes in the ice, allowing water to flow through the snow, melting it and spreading in a way that is energetically favorable,” Mc Keown said. “On Europa, we believe a subsurface brine reservoir could have erupted [after an impact] and spread through porous surface ice, producing a similar pattern.”

The team informally named the feature on Europa Damhán Alla, Irish for “spider,” to distinguish it from Martian spider formations.

To test their formation hypothesis, the team also conducted field and lab experiments, observing lake stars in Breckenridge, Colo., and recreating the process in a cryogenic glovebox at JPL, using Europa ice simulants cooled with liquid nitrogen.

“We flowed water through these simulants under different temperatures and found that similar star-like patterns formed even under extremely cold temperatures (-100°C), supporting the idea that the same mechanism could occur on Europa after impact,” Mc Keown said.

PSI’s Lesage modeled how a brine pool might behave beneath Europa’s surface after this impact, and the team created an animation illustrating the process.

Observations of Europa’s icy feature have been limited to images from the Galileo spacecraft from 1998, but the team hopes to resolve this question with higher-resolution imagery from the Europa Clipper mission, a NASA spacecraft scheduled to arrive at the Jupiter system in April 2030.

“While lake stars have provided valuable insight, Earth’s conditions are very different from Europa’s,” Mc Keown says. “Earth has a nitrogen-rich atmosphere, while Europa’s environment is extremely low in pressure and temperature. In this study, we combined field observations with lab experiments to better simulate Europa’s surface conditions.”

Looking ahead, Mc Keown plans to investigate how low pressure affects the formation of these features and whether they could form beneath an icy crust, similar to how lava flows on Earth to create smooth, ropy textures called pahoehoe.

Although geomorphology was the main focus of this study, the findings offer important clues about subsurface activity and habitability, which are crucial for future astrobiology research.

“Using numerical modelling of the brine reservoir, we obtained constraints on the reservoir potential depth (up to 3.7miles below the surface) and lifetime (up to a few thousands of years post-impact),” Lesage said. “This is valuable information for future missions looking for habitable environments within icy shells.”